lucidity and obfuscation

gestalt-shift insights

the waking self & its aberrations

lucid dreams

Green’s pioneering work

tackling anomalies

One should not be surprised if the concept of genius is suffering a gradual debasement. It is too much at odds with the mediocratic tenet of homogeneity — according to which all are fundamentally the same, differing from one another only in superficial ways. The term is more likely these days to be used to refer to a comedian or footballer than to a scientist or a composer.

The 1996 Chambers Dictionary has this entry for “genius” (my italics):

(1) someone who has outstanding creative or intellectual ability

(2) such ability

Two decades later, the online Oxford English Dictionary has those two senses in the opposite order:

(1) exceptional intellectual or creative power

(2) exceptionally intelligent or able person

The OED gives the following illustrative uses for (1):

“she was a teacher of genius”

“that woman has a genius for organisation”

The ranking has been reversed: the general faculty, apparently possessable by those with relatively humdrum occupations, now takes linguistic precedence over the unusual individual.

This presumably satisfies the ideological restriction on notions that smack of elitism. Out-of-date concepts which (regrettably) retain an aura of glamour must be redefined to suit pseudo-egalitarian requirements. [1]

Regarding the version of “genius” that is currently in retreat but still occasionally used: many people seem to have a simplistic idea of what it takes to be one. According to one popular model, all that is required is an increase in the magnitude of certain qualities which everyone already possesses in some measure. Make the particular qualities pronounced enough, and you get to genius.

But a better way to understand the concept — assuming we’re applying the word to (say) Gauss or Picasso, rather than John Cleese or Wayne Rooney — may be that a genius has a particular capacity, which on a certain level can seem obvious or unremarkable, but which no one else has. [2]

A genius, on this understanding, is a person uniquely capable of making a leap ‘off the path’. With hindsight the leap may seem simple or obvious, but at the time no one else was, apparently, capable of making it.

A potential leap of this kind is made possible by preceding leaps. Nevertheless its actual occurrence may go on not happening for decades. During that time there may be clear pointers towards it. Yet it is not until a genius comes along that the leap actually happens.

The performance of something simple yet astonishing points to genius consisting in a special x-factor, rather than just a turn-up of the volume button for one or more qualities.

Observing a new phenomenon, describing it, naming it: these are actions that can be achieved by means of increased effort or attention. More perspiration than inspiration, perhaps. An act of genius, on the other hand, as in the case of Einstein’s revisions of the ideas of space and time, seems to involve making a conceptual leap that causes one to see something familiar in a radically different way.

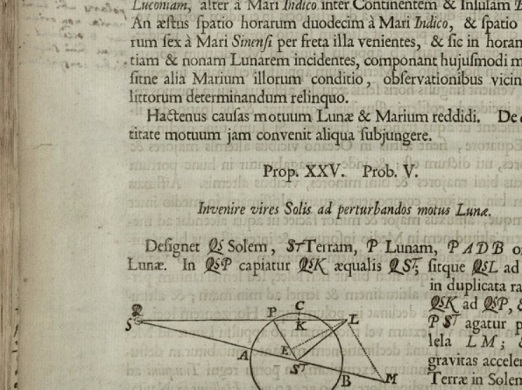

Take Newton’s leap with regard to gravity. That there was something making objects fall down had been recognised. The something had been named “heaviness”. That there was another something making the planets move in their orbits had also been noted. This something had been given the term “motive power”. Newton’s gestalt-shift insight was to realise that the two somethings are the same. His act of re-perception was described (some decades later, by which time the term “gravity” had come into use) by his friend Henry Pemberton.

As [Newton] sat alone in a garden, he fell into a speculation on the power of gravity.

That, as this power is not found sensibly diminished at the remotest distance from the centre of the earth to which we can rise, neither at the tops of the loftiest buildings nor even on the summits of the highest mountains, it appeared to him reasonable to conclude that this power must extend much farther than was usually thought.

Why not as high as the moon, said he to himself?

And if so, her motion must be influenced by it; perhaps she is retained in her orbit thereby. [3]

With hindsight, it may seem a simple association to make. Why should the thing that pulls an apple towards the earth not also generate the centripetal pull that produces the orbit of the moon? Yet apparently the connection occurred to none of Newton’s contemporaries. Even Newton himself appears not to have arrived at the insight in one fell swoop, as in the apocryphal apple story, but to have gradually come to it over a period of years.

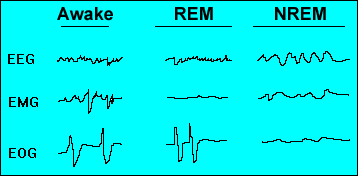

Sleep takes up a third of our lives, yet remarkably we still have little idea what its purposes are. Recovery is one of them, but this could presumably be achieved just by resting.

The paradoxical phase of REM sleep, during which most dreams seem to take place, presents a particular challenge [4]. The oxygen consumption of the brain is high during REM sleep — higher than when solving maths problems. Clearly the organism must gain something by cutting itself off from its environment to the point that fictional experiences are generated. But apart from hints that doing so may aid memory formation, we are as much in the dark as we were over a century ago when Freud wrote his Traumdeutung.

The sleeping self remains something of a mystery because of its lack of accessibility, but appears to be rather like the waking self, indulging in loose thoughts, associations and imaginings — except that something crucial is missing. This missing something becomes particularly noticeable during REM sleep. The self gets drawn into the action of the dream, which takes on a life of its own and appears more real than mere imaginings. We seem to lose a crucial element of our waking consciousness (rationality?) as well as access to facts and memories which in the waking state we are certain of.

Referring to an absence of ‘rationality’ begs the question of what this capacity of the normal waking state consists in. Rationality may seem an obvious idea, but in practice it is almost impossible to define, and the mechanism by which the brain imposes it on mental activity is unknown. Determining when someone is rational and when not is far from straightforward, as those who attempt to diagnose mental illness know. Normal rationality has its limitations, but the distinction between those defects that are an acceptable part of waking cognition and those that aren’t is somewhat arbitrary.

Research on sleep has concentrated on the question of function, viewed from the neurophysiological perspective. Neurons grown in a Petri dish show signs of needing ‘sleep’, suggesting there is something about the activity of neural networks that requires definite ‘off’ periods. As far as dreaming during REM periods is concerned, there is a wide range of suggestions as to what the body gains from this. The brain may run simulations, testing hypothetical scenarios without the interference of input from outside. Possibly the process benefits from the absence of conventional rationality, which could restrict some of the insights that can be made.

Or perhaps quasi-experiences are generated in order to test whether modifications to the brain, made during non-REM sleep, are working satisfactorily. Indeed, the point of REM sleep may be purely to give relief from periods of non-REM sleep and its rest/repair function, perhaps because quiescence puts neurons into an unnatural state which is damaging if it persists for too long.

But aside from the issue of function, sleep and dreaming also raise important questions about the normal cognitive processes of the waking state. There are questions (a) about how ordinary thinking proceeds: how do internal propositional states combine dynamically to generate useful end products? (For example: you believe most plants contain chlorophyll; and you believe chlorophyll contains magnesium; how do neurons generate from this the judgement that most plants contain magnesium?)

And (b) about how visual perception works: how does the mind, starting with neuronal signals, come to believe in the existence of a three-dimensional world, so that it is experienced as a visual ‘outside’?

The mental activities of sleep, consisting of shadows and distortions of normal cognitive function, thus highlight two fundamental issues about the mind.

• What is rationality? Is it an additional feature imposed on mental content, possibly a checking or censorship process? Can it be considered a unitary faculty, or is it more naturally conceived in terms of several elements?

• How does the mind generate the experience of external objects from the input of raw sense data, and compose a collection of these into a visual landscape? How much top-down processing — what Richard Gregory called perceptions as hypotheses — is involved in this?

Dreams might seem a fertile area to investigate these issues, but have traditionally been hampered by the same difficulty as that of psychosis: obtaining meaningful information from subjects about their experiences is problematic, if they suffer from cognitive defects during those experiences. There is, however, a possible way around the problem.

A lucid dream is a dream in which the dreamer is aware he is dreaming. Here is an example.

Strolling along in some seaside resort I realised it was a dream. The sea looked dull, which struck me as most unusual for a lucid dream, although I noticed a glow developing to the east. I gazed down at the beach far below, and considered jumping, but demurred at the thought of the unpleasant falling sensation, which would doubtless be real enough although I knew I could not hurt myself.

I walked on until I came to a path, which I descended. Noisy band music was playing, and I became aware of a cool breeze — a definite thermal sensation, I reflected, and decided to investigate other effects.

On reaching the lower promenade I tried hitting my leg with a stick; the sensation felt fairly realistic on the first stroke, but diminished to nil thereafter. I paddled in the sea, noting the coolness of the waves. My next aim was a gustatory sensation. Espying a jar of smallish (raw) plums on a counter I took one and began eating. The yellow flesh had a distinct plum flavour, although not quite as intense as one would expect in waking experience.

While still eating (the plum increasing in size) I awoke ... [5]

Insight — awareness of status — is the crucial characteristic of a lucid dream. Once you have insight, the quality of the experience typically becomes very different from that of an ordinary dream: clear rather than murky or muddled, realistic rather than fantastic, detached rather than emotive.

The point that awareness is the key characteristic has been subject to confusion, as is perhaps normal when there is resistance to a novel phenomenon. Various authors have conflated it with other supposed features of lucid dreams, such as visual or emotional intensity (lucid dreams can be elating or even euphoric), or ability to control the dream. However, lucid dreams are often emotionally neutral, and the dreamer may have relatively little control over what is experienced, beyond being able to move his dream body.

The notion of “aware” is obviously subject to some latitude of interpretation, but nevertheless appears to be crucial. Awareness of the true state of affairs (that one is asleep), to the point that a more normally rational version of the self emerges within the dream, appears to significantly change the quality of the dream, so that a separate category becomes appropriate.

There is clearly something paradoxical about a person possessing most of their conscious mental faculties while being asleep — which is one of the reasons lucid dreams appear to have considerable scientific potential. It should nevertheless be noted that the level of rationality, while unusually high, is not up to the full waking level. Although clear that he is dreaming, and able to think rationally about the dream action, a lucid dreamer remains slightly out of focus about reality outside the dream. For example, there is often difficulty in remembering the location of one’s sleeping body.

Four decades after the phenomenon began to gain popular currency, it remains neglected and somewhat misunderstood. One obstacle to comprehension is that unless a person has had at least one lucid dream, it can seem virtually impossible to convey the idea to them, rather in the way that it’s difficult to communicate the subjective sensations of giving birth.

Partly because of this, it is difficult to obtain reliable data on incidence, but it appears that at least 5 percent of the population, and possibly a much higher proportion, have had lucid dreams – so the phenomenon is not confined to the psychologically unusual. Moreover, it appears possible to train people to have them, using methods such as keeping a dream diary, or trying to maintain alertness while falling asleep.

Lucid dreaming represents an intermediate condition of rationality/consciousness between (a) the normal waking state and (b) normal REM sleep. Because of this, and because the lucid dreamer is relatively clear-headed about what he is experiencing, the phenomenon is potentially capable of shedding light on processes such as consciousness, rationality, perception, and mental illness, as well as on sleep itself.

Before laboratory research on it could become a possibility, it was necessary explicitly to recognise lucid dreaming as a psychological phenomenon, and to highlight some of its special features. Tying together various people’s reports of similar-sounding experiences prior to the existence of the concept, and positing that there was a distinct and novel phenomenon involved, required an intellectual leap.

The mere act of writing about one’s own lucid dreams, or of including them in an anthology of peculiar dreams, or in a practical guide to dreaming, does not amount to the leap required to see them as an important phenomenon.

Thus French orientalist Hervey de Saint-Denys’s 1867 book Dreams and the Ways to Direct Them: Practical Observations (originally published anonymously), which contains descriptions of a number of Saint-Denys’s own lucid dreams, doesn’t represent the “first book to recognise the scientific potential of lucid dreams”, as a recent version of the Wikipedia article on lucid dreams claims. As the title suggests, the book was primarily intended to provide suggestions for controlling one’s dream life, including how to defuse nightmares, as well as describing a number of Saint-Denys’s more colourful dreams, among which lucid dreams were merely one category.

Similarly, although Dutch psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden was the first to apply the term “lucid dream” to a dream in which one is aware one is dreaming — in a 1913 paper describing various categories of his own dreams — he didn’t explicitly propose it as a class of special dream that can occur to the average person. Nor did he suggest that it represents an important cognitive state, capable of being used by experimenters to shed light on the processes of sleep.

Becoming aware of an unusual type of experience of one’s own, and/or giving it a name, doesn’t amount to recognition of a general phenomenon. If Oedipus had been the first man to note the possibility of sexual attraction towards one’s mother, we still wouldn’t give him credit for recognising this as a general feature of male psychology. [6]

Nor do prescient observation, or recognition of a curiosity deserving attention, in themselves constitute scientific advance. The publication of Charles Darwin’s journal of his expedition, for example, highlighted one of the puzzles that would later help lead Darwin to profound theoretical insight: that of the Galapagos finches.

The remaining land-birds [of the Galapagos Islands] form a most singular group of finches, related to each other in the structure of their beaks, short tails, form of body and plumage ... The most curious fact is the perfect gradation in the size of the beaks in the different species ...

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends. [7]

Yet if Darwin had not published The Origin of Species some years later, we would not describe him as the father of evolution on the strength of his journal alone, and it might well be Alfred Russell Wallace’s name that would now rank foremost in the annals of biology.

That Celia Green’s 1968 book was the real ‘game changer’ for lucid dreams can be deduced from the fact that all laboratory research on the topic post-dates its publication, and from the fact that most of those working on it in the decades following credit the book with having directly stimulated their own research.

Green was the first to put together the various different individuals’ lucid dream accounts that had been published to date, recognising they represented a single phenomenon; and the first to treat the topic in a scientific manner, attempting to delineate its most common features and making specific suggestions for laboratory research.

Two elements of the book were particularly significant with regard to subsequent research.

1. Green predicted that lucid dreams would be found to be correlated with the REM stage of sleep (rather than being associated with, say, transient periods of semi-wakefulness). This represented the first useful proposal for empirical research, taking lucid dreams out of the realm of the fantastic and into the realm of hard-edged science.

2. Green speculated that, in spite of the paralysis of the REM state, there might be sufficient bodily control during lucid dreaming for signalling to be possible between the dreamer and an observer in the laboratory. This was a distinctly practical suggestion for increasing measurability of the dream state.

Green planned to test these ideas, and others, by going on to do electrophysiological research on lucid dreams and other anomalous experiences, and hoped that her preliminary ground-breaking research (produced on a shoestring budget) would make her eligible for academic appointments. However, apart from a few positive book reviews, the establishment pointedly ignored her. Instead, her ideas were taken up by other researchers, already with university positions, who used them to help make careers for themselves.

Green’s prediction that lucid dreams would be found to be associated with the REM state was confirmed by experiments carried out in North America [8]. Her lucid dream signalling idea was first experimentally realised in 1975, with a dreamer moving his eyes several times in quick succession to communicate that he was lucid [9]. It has since become a standard tool of dream research.

The feat of communicating with the external world from within a dream, in accordance with a waking intention, was a major achievement. This ability to remember instructions, and to act out prior intentions, provides clear evidence that there is a great deal of difference between the lucid dream state and normal sleep processes.

Green’s book was also the first to identify (and name) the phenomenon of false awakening — now a staple feature of audiovisual entertainment.

I dreamt I saw a collection of weapons in the wardrobe of my mother’s room (across the corridor from mine) and remember thinking they were Viking.

Then I ‘woke up’, as it were, and, still in my dream, went out of my room and into my mother’s and opened the wardrobe. To my disappointment I recall seeing nothing but clothes. While I was looking in at the wardrobe my mother opened the door of the room and asked what I was doing.

As far as I remember the dream ended there ... [10]

It’s not only false awakenings that have become a trope of popular culture. Lucid dreams themselves are increasingly referenced in modern entertainment, from sci-fi movies to children’s cartoons.

Green deserves credit for being the first to put the phenomenon of lucid dreaming on a formal scientific footing. Yet, like other pioneering women in history, she has received negligible reward for her achievements.

The research on lucid dreams that has been carried out by others since Green’s initial study has generated little that could be described as advancing understanding of the mind. The scientific potential of the phenomenon remains largely untapped.

The best way to advance understanding of a topic is to tackle the anomalies. Look at the aberrations of any phenomenon, and you are likely to gain important clues about the phenomenon itself. Take sex, for example. To understand sexual drive, consider the deviations from the conventional version, and you may come to appreciate that a whole range of interests and preoccupations, beyond the obvious factor of attraction to the opposite sex, are probably just as intrinsic to it: narcissism vis-à-vis one’s own gender, object-fixation, desire to dominate or be dominated, need for role-playing, and so forth. The key underlying features of any phenomenon tend to become more visible at the margins.

The principle that one should concentrate on anomalies is, however, often ignored. It’s usually considered easier to look in detail at what has already been worked over, rather than departing for problem areas. Your work is more likely to be understood; more likely to be accepted. You are more likely to get a result, however feeble. In the sausage-factory model of contemporary academia, these considerations take on such a weight that studying anomalies becomes almost impossible.

Nevertheless, progress on understanding mental processes is, as in other areas, more liable to be forthcoming by researching the anomalies. The difficulty with looking at mental illness, the most obvious anomaly, is that interacting constructively with subjects is problematic. Patients with brain damage who are willing to cooperate with researchers provide some useful insights, but are obviously few and far between.

That leaves anomalous phenomena experienced by non-psychotic subjects, under relatively normal conditions (i.e. not drug- or alcohol-induced). Unfortunately, such anomalies have often been viewed with suspicion, partly because of their cultural associations, but perhaps also because they are felt to be threatening in some way.

The most obvious anomalies of cognition – leaving out those of psychosis, brain damage or drug experience – are dreams and hallucinations.

A future article will look at hallucinatory experiences and find that similar considerations apply as in the case of lucid dreams. There exist paradoxical phenomena which appear to have important implications for the understanding of normal mental processes, but which have been treated with neglect, derision and obfuscation.

Celia Green should be given a stipendiary fellowship in recognition of her contribution to the field of sleep research, and her contribution to the potential understanding of normal cognition.

She should also be given funding for electrophysiological research on lucid dreams. As pioneer of the topic, she is more likely to make significant progress than those who have merely followed in her footsteps.

1. By “pseudo-egalitarian” I am referring to a system that ostensibly subscribes to egalitarian ideology, while being run by an elite which uses that ideology to protect its position. Communist Russia provides one example. The contemporary British version was described by George Walden in The New Elites, and appears to be a current feature of most Western societies. For more discussion of this phenomenon see here.

2. Obviously excepting any other genius who happens to be in the vicinity.

3. Henry Pemberton was the editor of the third edition of Newton’s Principia. The quotation is taken from his View of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophy, published in 1728.

4. The REM phase of sleep is sometimes referred to as “paradoxical” sleep, because most of the body is in a quiescent state, while the brain’s activity is very similar to that of the waking state.

5. Quoted in Celia Green, The Decline and Fall of Science, Oxford Forum, p.106.

6. Oedipus is of course a mythical character; there is no evidence he existed.

7. Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches, 1845, chapter 17.

8. E.g. by Ogilvie, Hunt, Kushniruk & Newman (1983), Lucid dreams and the arousal continuum, Sleep Research 12.

9. Keith Hearne (1978), Lucid dreams: an electro-physiological and psychological study, PhD thesis, University of Liverpool.

10. Quoted in Celia Green, Lucid Dreams, Institute of Psychophysical Research, p.117.