weekend notes #12

Once upon a time there was a world which was culturally productive but rather inegalitarian. Then the inhabitants invented ‘social justice’ as a device for legitimising their mutual hostility, and soon things were in a pretty pickle.

Oxford’s “thick rich”

average GP: inadequate

Thatcher as dung clearer

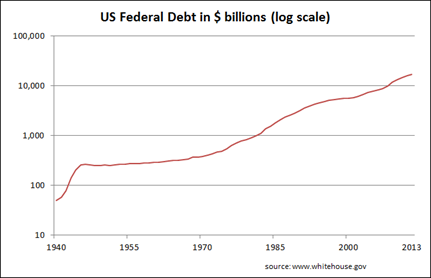

exponential debt

Live sex!

Oxford’s director of undergraduate admissions, Mike Nicholson, claims the university is working hard to weed out “thick rich” applicants.

I really don’t care whether candidates are poor and bright or rich and bright. I want the bright ones. If they’re thick and rich, they’re the ones I’m hoping our process can exclude.

When I was teaching at Oxford in the nineties and involved in selecting applicants for economics-related courses, I didn’t hear dons use the phrase “thick and rich” in conversation, let alone in speeches. Things have evidently become more demotic there since then.

When I was teaching at Oxford in the nineties and involved in selecting applicants for economics-related courses, I didn’t hear dons use the phrase “thick and rich” in conversation, let alone in speeches. Things have evidently become more demotic there since then.

How geared to ability is Oxford’s admission process by now? Probably no more than ever. It was always riddled with biases of various kinds, based on the preferences of interviewers or the style of entrance test, and will no doubt continue to be so. Attempts to correct for one kind of prejudice usually generate another kind. There’s a financial bias, of course. Overseas students pay more, and if the proportions have been increasing there is an obvious possible explanation – though I have no idea how far this applies in Oxford’s case.

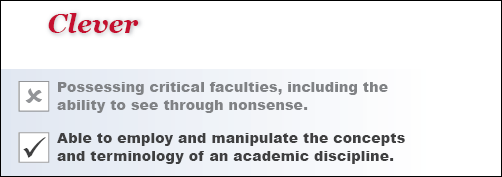

The theory that Oxford, and other elements of the establishment, were once full of “rich thickos” – but are nowadays more populated by the genuinely intelligent – seems to be one of those appealing myths that buttress mediocracy, like the fable that Victorian aristocrats habitually raped their servants. A better way to characterise the change that has taken place at Oxford and elsewhere may be in terms of the expulsion of one kind of intelligence, and its substitution by another.

The theory that Oxford, and other elements of the establishment, were once full of “rich thickos” – but are nowadays more populated by the genuinely intelligent – seems to be one of those appealing myths that buttress mediocracy, like the fable that Victorian aristocrats habitually raped their servants. A better way to characterise the change that has taken place at Oxford and elsewhere may be in terms of the expulsion of one kind of intelligence, and its substitution by another.

For purposes of illustration, consider two extremes.

Type A: e.g. Dorothy Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey, or Percy Blakeney in The Scarlet Pimpernel. Superficially light-hearted, apparently unassuming, but with an underlying seriousness. Analysing things on more levels than just the most obvious.

Type B: e.g. Dracula’s Van Helsing, or Brains from Thunderbirds. Good at being logical, but relatively little imagination, and a tendency to miss the bigger picture.

Type B: e.g. Dracula’s Van Helsing, or Brains from Thunderbirds. Good at being logical, but relatively little imagination, and a tendency to miss the bigger picture.

Type B may be the better choice if you’re looking for ability to reproduce the techniques of mathematical economics, or analyse literature using the standard perspectives and buzzwords. But excluding type A on the grounds that he or she doesn’t exhibit the stereotype of earnest, boffin-ish intelligence (or other version of being “bright”) is likely to leave your organisation a poorer place in terms of both atmosphere and productivity.

I have no wish to promote a bias against the kind of person popularly labelled as “nerd”. They probably suffer enough prejudice as it is.

Nor am I advocating a preference for people who are glib at interviews. A bias against those who come across as highly articulate may of course appeal to egalitarians, as likely to generate the anti-private-school selectivity many of them seek, and I came across a few apparent instances of this kind of bias when involved in admissions. I also thought I detected a hint of counter-strategy on the part of some applicants: not making it too obvious how socially adept one is, to avoid arousing resentment. Are they teaching that at Eton nowadays?

Things are obviously more complex than the simple A-B model above. Nevertheless, a crude hotting-up of the search for ‘intelligence’ should be avoided, if the concept being used is simplistic – particularly when the search is coloured by tendentious assumptions e.g. that ability is not inherited.

● I recall reading a review of the biography of colourful don Maurice Bowra, in which the reviewer (I think it may have been Sir Anthony Kenny) expressed satisfaction that the Oxford of Bowra’s time had “vanished forever”. The hostility implicit in such rejoicing over the disappearance of the old – also exhibited by many of the figures of New Labour – seems fuelled by ideological bias rather than anything rational.

Individuals like Bowra had their bad points as well as their good but so do current dons. The atmosphere at Oxford has changed since Bowra’s time, but to label it as better is to elevate an arbitrary set of preferences into something with unquestionable objective merit. But then, identifying with whatever the currently fashionable ideology happens to be, without detachment or perspective, tends to be a defining characteristic of contemporary academics.

Mike Nicholson hints that many of the people who got in “20, 30, 40 years ago” might not do so now. Suggesting that an earlier policy is at variance with a current one can backfire unless it’s clear that the current policy is a good one. I wonder whether the youthful versions of Mr Cameron or the Mayor of London would be admitted if they applied now. Or would they be regarded as “rich” and hence as more likely to be “thick”?

The government has proposed that medical practices should be ranked

into four “quality categories”:

into four “quality categories”:- Outstanding

- Good

- Requires Improvement

- Inadequate

and the assessments are to be nailed up in surgery waiting rooms.

Rather humiliating to be slapped with either of the last two ratings. How are they going to ensure the assessment is correct? “Success” and “failure” are relatively determinable for hospital operations, though even there the process of assigning numbers is dubious and liable to generate distortions. For general practice it would seem near-impossible.

No doubt some surgeries are inadequate in the sense the Department of Health means, but whether that can reliably be identified by formal inspection process is another matter. Assessing whether treatment is effective must be done either:

a) by someone who is not a member of the medical profession, in which case doctors will complain that he/she is not qualified to judge; or

b) by someone who is a member of the club, in which case we have the problem of medics being reluctant to criticise one another.

The latter issue has recently come to public attention in connection with various hospital scandals, but has been around for decades. Some modern versions of the Hippocratic Oath involve doctors having to swear “loyalty to the profession”.

Patient satisfaction could be an indicator of good versus bad, but it’s doubtful whether the profession would allow much weight to be given to this. Its monopolistic control of drugs and other medical technology has allowed it to acquire a degree of insulation from client preferences which it is unlikely to risk by exposure to thorough patient assessment.

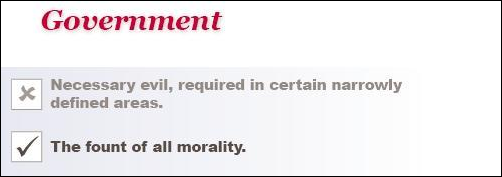

One of the key rationalisations for the profession’s paternalistic (and increasingly collectivist) approach has always been that patients are supposedly unable to make meaningful judgments about clinical matters. As the British Medical Association says in its response to the proposals,

Ratings must differentiate between the quality of experience that the patient perceives and the quality of care that an expert observer might consider has been delivered. [italics mine]

(You may feel you’ve been treated appallingly by a doctor, but his colleagues may well reckon he did an okay job.)

I have some sympathy with doctors’ reluctance to be assigned simplistic scores. Still, if a profession signs up to marriage with the state it cannot be surprised when – after an interval – it starts to be seriously interfered with, assessed, criticised, and generally told what to do. The assumption, back when the NHS was created, that medics would continue to be pleasingly independent was, with hindsight, naive.

Assessment of the kind proposed misses the more important issue that at present all GPs are “inadequate” – or rather totally unacceptable – because they have carte blanche to override the wishes of their clients. With power entirely on the side of the providers, the abuses that are coming to light are no surprise, and probably the tip of the iceberg.

There’s something I keep reading about the late Margaret Thatcher. Apparently what people found most irritating about her was her sense of certainty – the feeling one got that she thought her viewpoint was right and that others were most likely mistaken.

There’s something I keep reading about the late Margaret Thatcher. Apparently what people found most irritating about her was her sense of certainty – the feeling one got that she thought her viewpoint was right and that others were most likely mistaken.

But if there’s a bad situation brought about by a damaging philosophy that has become dominant, and you bring in someone to treat the problem, a conviction that the prevailing outlook is mistaken is surely one of the qualities they need to have. In other words, an apparent ideology opposed to the dominant one is going to be a fairly inevitable characteristic of a person hired to sort out a serious mess. Seeming arrogant, and obliviousness to standard objections, are additional likely features.

Pursuing consultation and consensus in such a situation may make everyone feel more warm and cherished, but is likely to leave the status quo intact.

(Something similar was probably true of the reformation of Eastern Europe. Without a strong belief – perhaps excessive – in the power of markets to cure all ills, places like Poland and Slovakia might today still be looking like 1960s East Germany.)

Probably only a woman could have done the job. While women often seem to be more concerned about social disapproval than men, there is a sense in which practically no man will risk complete ostracism for the sake of his beliefs, while an exceptional woman sometimes will.

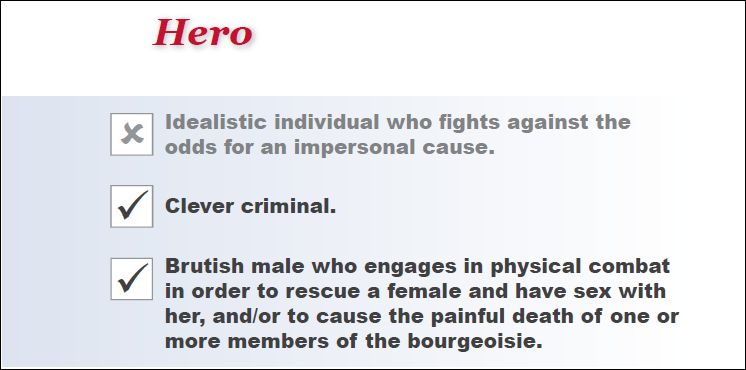

Thatcher didn’t get much respect from the British establishment. She seemed at times like some local muscle hired to clear the dung from the royal stable; looked down on by the courtiers, and utterly shunned after the work is finished.

Despised and hated by the cultural elite while in power, and regularly playing the role of arch-villain in its subsequent moans about cultural deterioration, the image of her which its cumulative vitriol has left us with is that of grotesque hate figure.

“Thatcher’s children are everywhere,” claimed one of her obituaries. I can’t say I’ve come across many of them myself. By contrast, Wilson’s and Blair’s children seem to be ubiquitous – dominant in every upper layer of society, and the standard model in universities. At the height of her power, Thatcher claimed victory for the world view she championed. With hindsight, the brief resurgence of that world view looks like little more than a blip.

● The right-wing brand still “reeks”, a journalist claimed the other day, notwithstanding recent efforts to ‘sanitise’ it. And so the Conservatives twist and turn this way and that, in a hopeless attempt to reconcile the values that distinguished them with the values demanded by the new hegemony. But if conservatism is no longer capable of being sold to the electorate without having to be reconstructed to the point of inversion, we have journalists – and other members of the cultural elite – to thank for the negative marketing which led to this.

If one endlessly pumps out propaganda implying that the various elements of conservatism (markets, sovereignty, minimal intervention, support for capitalism, etc.) are morally suspect, then of course the average person will eventually not be able to hear any reference to them without getting a bad feeling. It’s simple Pavlovian psychology and it has been used to great effect.

Thatcher was not the only person convinced of her rightness. She stuck out because she was relatively isolated and highly visible, in contrast to the army of the Left who started to take over the cultural citadels in the sixties and seventies. “We had work to do,” as Professor Catherine Belsey* put it. “There was a sense we might break through,” reminisces Professor Terry Eagleton.

Like the Apostles converting the West to Christianity, there was a movement of intellectuals determined to bring a new morality to rule the world, staunchly believing they were in the right. They succeeded, and they’re still in power. But with dominance comes the privilege of subtlety. You don’t have to wave a big flag, the consensus is already on your side. The job now is to keep sending out little reinforcement signals to maintain the status quo – an ideological subtext in a drama series here, a bit of reporting bias there. Behave as if the new ideology is universally agreed, the debate has moved on; and treat any apparent deviation as tremendously shocking. Oh, and keep any serious dissidents out in the cold.

Conservatism may be the superficial villain in the parables now told by the cultural elite, but classical liberalism and libertarianism are the likely real objects of hostility, judging by the particularly vehement reaction to the free-market elements of Thatcherism and by the recurrence of that reaction whenever there is a sign that one of the elements might be making a comeback. To directly attack libertarianism – a minority position – is to give it undesirable publicity. Hence the Tories are a convenient substitute target.

So-called ‘liberals’ sometimes like to claim libertarianism as their own. It is clear by now, however, that the modern Left are firmly on the side of the state, and hostile to its critics.

“This [the publication in 1969 of Althusser’s assertion that education is the main Ideological State Apparatus] meant that, as radicals, we had work to do on our own doorstep, instead of looking slightly out of place on other people’s picket lines.”

Terry Eagleton’s comment was made in a 2007 interview with the Sunday Times.

Problem: Peacetime democracies with interventionist states tend to generate exponentially increasing public debt levels which will, at some point, become unsustainable.

Problem: Peacetime democracies with interventionist states tend to generate exponentially increasing public debt levels which will, at some point, become unsustainable.

Possible solution: Introduce legislation to ban increases in government debt above a predetermined threshold, and require “extraordinary” measures for the threshold to be raised.

Does this work as a way of encouraging everyone to be more prudent, and to avoid abusing government’s ability to spend as much as it likes in the short run, regardless of revenue? Apparently not.

There’s not much sign that America’s latest instance of invoking the procedure had a restraining effect on expenditure before it cropped up. Nor does the debacle itself appear to have had a net sobering impact. It merely caused temporary havoc, and those who tried to use the occasion to exert pressure for spending reductions were lambasted as irresponsible.

“Obamacare” may or may not be a wonderful scheme for benevolent government intervention, but should it have been introduced when the US is already massively overspending on the attempt to manipulate unemployment down to 6.5%?

People having sex inside a big box? In a television studio? With a live audience? Afterwards discussing who did what to whom? The whole thing compèred by Mariella Frostrup?

People having sex inside a big box? In a television studio? With a live audience? Afterwards discussing who did what to whom? The whole thing compèred by Mariella Frostrup?

Are we in Bizarro-world?

No, but perhaps the Channel 4 execs have been cutting their coke with ketamine again.

The overall effect of Sex Box was mildly titillating (in a prurient, unsexy way – “did you ... you know ... you did? oooh!”) but not very informative. Exhibiting live sex is a bit pointless if you don’t actually get to see it.

One supposed aim was to counter the fictions of pornography with a bit of realism, but there wasn’t much realism on show except for the truism that couples who socialise after doing it tend to look smug.

The real point of the programme seemed to be to express the mediocratic position on sex, which is that it is now essentially a public rather than private affair. In a pseudo-egalitarian society, we are deemed to have a right to know about all the activities you are getting up to, and to express our opinion as to their moral and/or technical merits. If at present we choose not to install giant monitors with hidden cameras in every room of your house, it doesn’t mean we wouldn’t if we thought it socially desirable.

If one genuinely wanted to convey realistic information about sex, the following options could be considered.

A) Set up a website with videos of ordinary-looking adults having sex in pedestrian ways. The participants should not be attractive (probably best to use over-40s), the tone being prosaic rather than erotic. Given how exhibitionist everyone seems to have become, it should be easy to find willing couples. The Department of Health could act as webmaster, providing ancillary advice about contraception and STDs, as well as saucy techniques.

B) Have people discuss in detail the full range of their own sexual experiences, but without requiring them to have performed five minutes earlier. The ability to be analytical without normative assumptions would be helpful here, so novelists would probably work better than psychologists. The problem with this one is that it’s highly uncomfortable to talk with complete frankness about one’s sex life, particularly with thousands of Twitterers watching. Possibly more suited to radio.

● When members of an elite talk about making their world more available to those who are not like them, it is worth thinking about motivation – anything really worth having is not readily given away. In a world that generates phoney ‘oughts’ about sharing, one has to learn to look behind apparent generosity.

Has the particular advantage they are talking about become debased? Are they in fact offering something different? A world of homogeneity as a sop, in which no one will have what they had? Will their actions mean that things become more difficult for potential rivals?

Taking would-be egalitarian behaviour at face value can be dangerous. What is the real objective? What are they trying to get past you? Is it a poisoned chalice? A Trojan Horse? Are you a pawn – or a mark?

A healthy cynicism is advisable, especially in a world where reality has become taboo and dishonesty the norm.

● We hope that you found this year’s commentaries interesting, and that they raised awareness of our position. In which case, why not do something to help. If not able to contribute directly you could purchase one of our books, or publicise our existence by telling others about us.

If you’re a writer looking for ‘inspiration’ who hasn’t yet bothered to give us a mention or other benefit, you are somewhat less welcome. As for you other Slim Shadys, trying to dress as lamb ...

If you’re a writer looking for ‘inspiration’ who hasn’t yet bothered to give us a mention or other benefit, you are somewhat less welcome. As for you other Slim Shadys, trying to dress as lamb ...

published 2 December 2013

Academia has become mediocratised, resulting in the exclusion of those who don’t conform to the required models. My colleagues and I are prevented from contributing to debates on key issues in science, philosophy and social policy. Ideological bias means the debates are highly skewed towards reductionist and statist perspectives.

The ability to comment on the web is not a substitute for mainstream publishing from the position of an academic post. We are waiting to start being productive academics. Our web writings are intended to draw attention to our existence and objectives.

We need financial support, and people to come and help with our efforts. If the idea of individual academics operating without institutional endorsement seems strange, it’s a sign of how dominant sausage-factory thinking has become. Collectivisation has taken its toll: it is time for a re-think.