‘normal’ science

Robert Winston, professor of fertility studies and former head of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, was recently reported as claiming that he avoids hiring graduates with firsts for his research team.

... in my laboratory I have appointed scientists on the whole that didn’t get first-class honours degrees, deliberately, quite specifically, because, actually, I would rather have young people around me who developed other interests at university and didn’t just focus entirely on getting that first. That’s been a very successful strategy. It’s produced a lot of useful science, because we’ve worked as a group of friends, as a team.

In subsequent Twitter comments, Lord Winston said he had been misquoted by The Times, and that there were people with firsts in his lab. Nevertheless, he reiterated that

Managing talent does mean spotting people who are capable of collaboration ... scientists who don’t work in a team with others are generally less likely to produce valuable results ... many people with poorer degrees may make better team players.

It’s an interesting idea that you might choose to hire those with lower, rather than higher, class degrees. Such a policy is at variance with the practice that used to prevail in the sciences, as far as I know, but perhaps things have moved on.

It is of course possible that Lord Winston wished to provide moral support to those with high-grade scientific minds who fail — for one reason or another — to achieve the traditional entrance requirement for an academic career.

Class of degree is certainly not an infallible indicator of intellectual ability, especially for those most likely to make major advances. Look at the innovators of the past and you see a sizeable proportion of non-conformists, some of them failing to impress during their education in terms of the standard measures, at least at certain stages or in certain areas. The mind of a typical innovator is apparently so idiosyncratic that he or she can easily fall through the cracks — especially perhaps within a system that is unsympathetic to the idea of exceptionality.

I also get the impression that university examinations may have been getting more pretentious and dishonest, and hence less useful as a discriminator. There is the well-known teaching idea that pupils need to be allowed to discover things for themselves, in a creative way, without being made to learn by rote. In practice, methods which claim to follow this theory tend to be just as prescriptive but in a concealed way, pretending to give a pupil freedom of choice while covertly coercing him to produce the ‘right’ answer, to the extent he is not just left floundering. Parallel to this, an analogous philosophy may have become influential in university teaching.

When I sat exams at Oxford for an MPhil there was certainly a hint of this. We were told that the papers were testing for “ability to apply the techniques of economic analysis” and not for rote learning, but this seemed dishonest since what was principally required was memorisation of a large number of academic models, many of them highly artificial.

It’s true that one of the interesting features of a high IQ is the ability to apply itself to whatever is required, in whatever area. On the other hand, there may be a limit to the extent an able person can contort himself to intelligently reproduce something, when the something is too obviously disconnected from reality.

But perhaps Lord Winston’s policy goes beyond sympathy for the unlucky, the idiosyncratically exceptional, or those who have difficulty dealing with the dishonesty of contemporary degree courses. Maybe his comments are telling us something about the state of science, and the kind of people now dominant within it.

The vast bulk of the research currently being carried out worldwide is clearly of the character which Thomas Kuhn termed “normal science”. In fact, it’s possible that all of it is now of this nature, at least to the extent it is carried on inside the university system.

No doubt there are some researchers who think of their own work as potentially revolutionary. But to have got to the position of being a paid academic within the present system they must have demonstrated a certain amount of commitment to the dominant framework without wanting to argue about fundamentals. A person seen as “too clever” or “difficult”, or considered incapable of collaborating with the other researchers — whether because he’s presumed to have problems himself collaborating, or because the other researchers would have what are euphemistically called “personality issues” with him — is unlikely to be hired, judging by Winston’s comments.

The versions of “cutting-edge” research which are ostensibly being carried on are (I suspect) mostly conventional, in the sense that they are ultimately rooted in the prevailing assumptions. Such research may well come to be interpreted, with hindsight, as “normal”, once we have had the next revolution — assuming we ever get another one.

The academic system we now have seems likely to promote a particular kind of intellectual: one intelligent enough to understand the established results, who communicates well, is reasonably sociable, can cooperate with others (preferably in large groups); but who doesn’t threaten other researchers, or the discipline as a whole, by going off into his own theoretical speculations, or otherwise looking as if he might actually make major advances.

Hence, major advances are what we do not get.

I doubt whether someone with the potential to overturn the key assumptions would be allowed to get very far in modern academia. The rule for career progression these days is: produce something that reinforces the winning model, add a few clever tweaks of your own, but never rock the boat. And don’t threaten the head of department by appearing to be cleverer than him.

But don’t worry, no one inside the system minds about this; it suits them quite well. The few people of exceptional ability who got in before things had deteriorated too much are all right, Jack. They aren’t going to attack the nice pseudo-egalitarian ideology — no gain in that for them. As for the rest, they’re happy to have things the way they are. A system created by mediocrities for mediocrities.

I have been reading Hugh Thomson’s entertaining account of the 2003 expedition that uncovered the full extent of the Inca site at Llactapata. Llactapata is down the road, so to speak, from Machu Picchu, and turned out to be a more significant component of the Inca Trail than had been realised.

At one point Thomson sidetracks to tell us about the hard-won discovery in the late 1990s of the Caral culture — the current candidate for the oldest civilisation in the Americas — by Ruth Shady Solís, at the time working outside the university system but in correspondence with academics at the University of Illinois.

At one point Thomson sidetracks to tell us about the hard-won discovery in the late 1990s of the Caral culture — the current candidate for the oldest civilisation in the Americas — by Ruth Shady Solís, at the time working outside the university system but in correspondence with academics at the University of Illinois.

Jonathan Haas was the distinguished Professor at the Chicago Field Museum, who, together with his wife Winifred Creamer, had taken an interest in Ruth’s work.

Ruth was determined to show that there was a ‘pre-ceramic context’ to some of the structures she was uncovering, even though this went against precedent. So she sent a sample of a [woven fibre bag] to Haas for dating: ‘No one else at the time thought that Caral could possibly be pre-ceramic,’ that is, that it could date from before 1700 BC when pottery was thought to have started in the Andes. Haas rang her in some surprise to say that she was right.

Science magazine were alerted and ran a major article on the subject, with Ruth credited as an author, together with Haas and Winifred Creamer. According to Ruth, Haas had suggested that publishing the article on Caral in Science, with his and his wife’s name attached — even though Haas and Creamer had never excavated at Caral — would subsequently make it easier to obtain funds for Caral ...

Ruth’s uneasiness at giving co-authorship of the article to Haas and Creamer was compounded when she discovered that on Haas’s Field Museum website the actual investigation of Caral was credited to Haas, while on his wife Winfred Creamer’s site at the University of Illinois, the discovery of ‘the oldest civilisation in America’ was likewise credited to Creamer. Moreover the detail that really stuck in Ruth’s throat was that Creamer was therefore nominated as the university’s ‘woman of the year’.

[pp.77-78]

Shady told Thomson, “Son piratas, realmente, the fact is they are pirates”.

I am sure this kind of piracy is not at all uncommon. In this case, its exposure led to some red faces, but there are probably many more incidents where misappropriation, and the resulting destruction of a career that might have been, never come to light.

● Brainteaser. Desirable results may lead to piracy. Undesirable results may lead to suppression. The following extract, publicised in 2010, is from an email sent by the head of a prestigious international institution to a colleague, confiding that he rubbished two papers that were critical of his own work. Which highly politicised scientific discipline may have had its position seriously distorted by his behaviour?

Recently rejected two papers [submitted to academic journal “X”] from people saying [my research organisation] has it wrong over [controversial topic A]. Went to town in both reviews, hopefully successfully. If either appears I will be very surprised, but you never know with [X].

● Given that the academic system has been developed so that promotion depends more on superficial CV presentability and on social networking, than on substance, or on the desire to make actual progress; and more on ability to impress with impenetrable gobbledygook than on saying anything meaningful, is it any wonder if those who rise to the top are distinguished principally by cunning and ruthlessness?

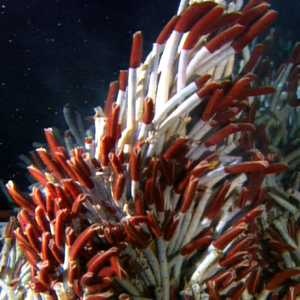

Another case of academic mischief I recently came across* concerns the deep-sea origins hypothesis. This proposes that the first life on earth may not have depended on light, as is usually supposed. In hydrothermal vent ecosystems, the primary source of energy is generated via the action of “chemosynthetic” bacteria that make sugar from carbon dioxide and water using the energy of hydrogen sulphide gas. It is possible that the earliest living things were chemosynthetic rather than photosynthetic.

Another case of academic mischief I recently came across* concerns the deep-sea origins hypothesis. This proposes that the first life on earth may not have depended on light, as is usually supposed. In hydrothermal vent ecosystems, the primary source of energy is generated via the action of “chemosynthetic” bacteria that make sugar from carbon dioxide and water using the energy of hydrogen sulphide gas. It is possible that the earliest living things were chemosynthetic rather than photosynthetic.

At the time the hypothesis was proposed (shortly after such ecosystems were first discovered), the origins-of-life field was completely dominated by Stanley Miller — the man who had performed the famous life-in-a-beaker experiment — and his supporters and acolytes. The establishment, it seems, were not best pleased with an idea that was completely at odds with what by then were regarded as the ‘foundations’ of the subject. As a result, the paper which attempted to present the hypothesis was stonewalled.

The controversial manuscript was not eagerly received; it bounced around for the better part of a year. First it was rejected by Nature, then by Science.

... Stanley Miller and his protégés were not [about to let] unsupported speculation sully their field. Hydrothermal temperatures were much too hot for amino acids and other essential molecules to survive, they said. “The hypothesis is a real loser,” Miller complained to a reporter for Discover magazine. “I don’t understand why we even have to discuss it.”

... Eventually the Corliss, Baross, and Hoffman manuscript was published, in a supplement to the relatively obscure periodical Oceanologica Acta, a journal that not one in a hundred origin-of-life researchers would see.

[Robert M. Hazen, Genesis, 2005, pp.98-99]

In other words, the research was buried.

Fortunately, someone seems to have recognised its significance and decided to alert others to it, so that eventually it got the attention it deserved.

● There is another dark aspect to this story. According to Jack Corliss, who as first-named author of the paper got most of the initial credit and fame, it was he who came up with the deep-sea origins theory. According to others, however, it was Sarah Hoffman who first proposed the idea in a term paper, which she was encouraged to circulate. Hoffman claims that Corliss appropriated what was essentially her research and assumed the lead role, although his principal contribution was his contacts in the field (he was one of the team which discovered the first hydrothermal vent ecosystem in 1977).

Hoffman, who must have been exceptionally insightful to come up with the original idea, sadly did not continue her career in science.

* via Robert Hazen’s very listenable audio lectures on abiogenesis

● Answer to brainteaser: the scientific discipline is climatology. At least one of the authors of the rejected papers left academia shortly afterwards, though it’s not clear how much this was due to the impossibility of getting his work published.

A few weeks ago, a new moon of Neptune was discovered by Mark Showalter of SETI, taking the total to 14. This one is only 18km in diameter, about the size of Phobos (pictured). The new moon’s name is S/2004-N-1, admittedly a little prosaic compared to its sisters Galatea, Larissa and Despina.

A few weeks ago, a new moon of Neptune was discovered by Mark Showalter of SETI, taking the total to 14. This one is only 18km in diameter, about the size of Phobos (pictured). The new moon’s name is S/2004-N-1, admittedly a little prosaic compared to its sisters Galatea, Larissa and Despina.

Earlier this year National Geographic asked a researcher at privately-funded SETI why the hunt for radio or microwave messages from extraterrestrials has come up empty so far. (It may of course just be that the signals coming from somewhere like Kepler-22b would be too weak to pick up using current technology.)

The famous Fermi Paradox asks just that: if intelligent life is so common then where are they? My personal opinion is that ... life is pretty common and even intelligent life might be relatively common but technological civilizations like our own may be relatively rare.

If every star had a planet with intelligent life just like our own, were long lasting and survive their technological development, and was altruistic and decided to signal its presence, we would have already detected something. So clearly intelligent life is not that common.

Now I do not wish to disparage the research of SETI. I’m fascinated myself by the question of life on other planets. I wonder, however, whether there is an element of anthropomorphism here. It seems to me that individuals with an intelligence somewhat different to ours might conceivably not be very interested in what the beings of another species had to say, or might estimate that the probability of benefit from making formal contact with an alien society was outweighed by the risks. Extraterrestrials of that ilk might decide it was better to keep shtum.

Isn’t it possible that those kinds of intelligence are predominant in the universe, with ours — constantly obsessing over what others are doing, whether next door, in Hollywood, or on other planets, and desperate to transmit our viewpoint to those not yet familiar with it — being the exception to the rule?

I think I should ask for money more often. It seems to irritate people.

Sometimes irritating people is a good thing. It draws attention to differences in viewpoint which would otherwise remain concealed.

I believe people are irritated by our requests not only because (a) they dislike having to refuse, or (b) they dislike being made to feel, even a little, that perhaps they ought to be doing something to help.

I suspect our asking for money annoys some people because it’s at variance with their preferred model of the situation, according to which we are a group of eccentric enthusiasts/idealists, excluded from social status not because academia (the environment that ought to allow people like us to be productive, if there is any point to it at all) is rotten, but because we actually like living in constricted and secluded semi-poverty, cut off from mainstream platforms.

In fact, none of us envisaged, when we started our adult careers, that we would be located as remotely from the centre of society as we currently seem to be.

Persons inappropriately relegated to inferior positions have to be careful to resist the tendency of others to regard those positions as legitimised through custom — an observation which you will find in leftist literature, though not usually applied to this particular situation.

published 4 August 2013

Lack of funding means I am limited to making brief comments on complex issues. Those with access to state finance, who could provide more detailed expositions from a similar perspective, do not.

Private capital is necessary for scientific and cultural progress. Modern institutionalised academia is not well suited to generating paradigm shifts. Those with surplus funds should regard it as a responsibility to support individual innovators, including those with unfashionable viewpoints – irrespective of whether they agree with them.

Oxford Forum is seeking patrons to provide financial backing. Donations support the work of Dr Celia Green, one of the few female geniuses there have ever been, and at present scandalously ignored by the intellectual establishment.